By Usman Hayat

Published in Dawn, November 03, 2021

Is Pakistan’s public debt sustainable?

Let’s try to answer this question in an apolitical manner and in relatively simple terms while examining the bigger picture.

Pakistan’s public debt profile

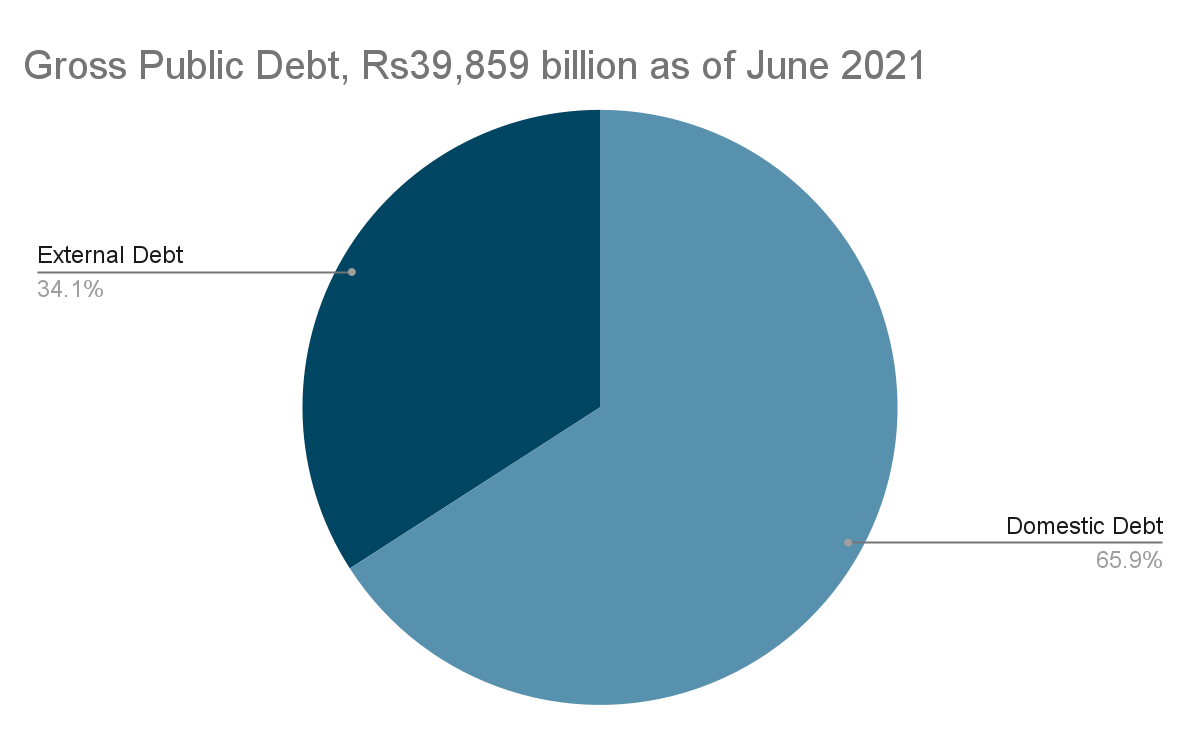

According to the debt bulletin by the finance ministry’s Debt Policy Coordination Office, Pakistan’s gross public debt was just about Rs40 trillion as of June 2021 — about one-third external and two-thirds domestic.

Domestic debt is mostly accounted for by Pakistan Investment Bonds, Treasury Bills, and the National Savings Scheme.

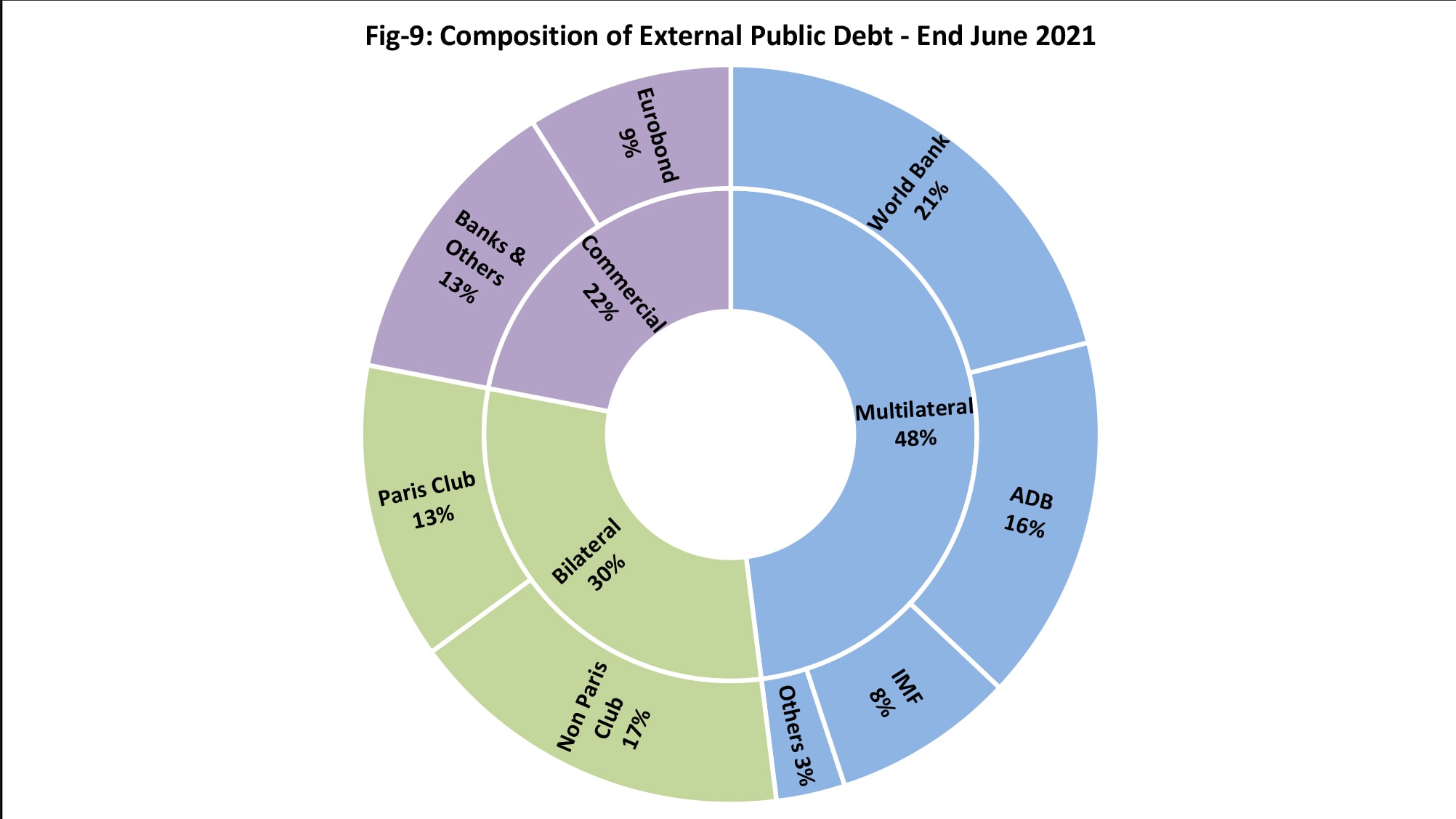

External debt, neatly summarised in the following pie chart provided in the debt bulletin, is mostly accounted for by multilateral lenders (the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, Asian Development Bank), bilateral lenders (Paris Club), and commercial lenders.

It represents a greater burden because it has to be paid in foreign exchange and the lenders are powerful entities and countries. The rupee-dollar exchange rate used in the debt bulletin as of the end June was Rs157; now that the dollar is climbing above Rs170, the external debt has increased.

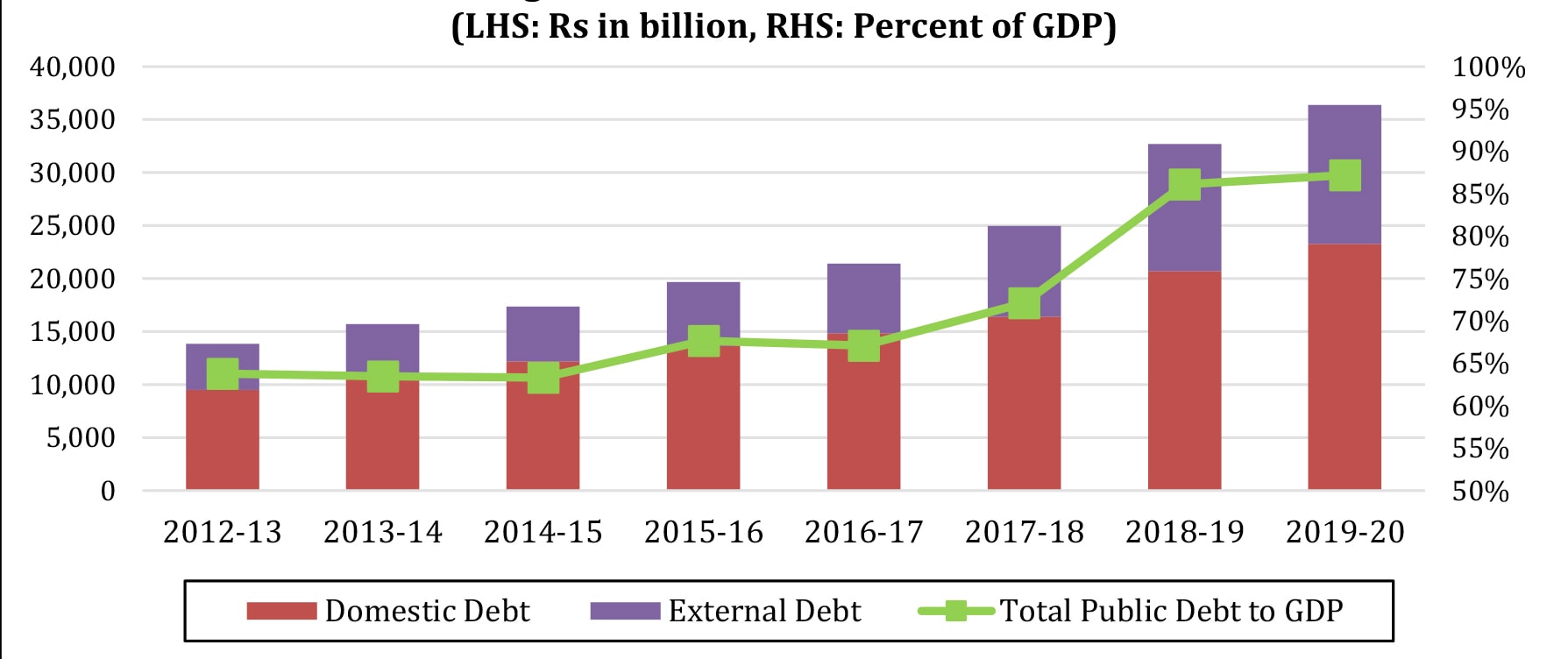

Pakistan’s debt relative to the gross domestic product (GDP) or the size of the economy has been rising as shown in the following bar chart provided in the Economic Survey 202-21, climbing above 80 in recent years which also reflects the impact of Covid-19.

However, it should be noted that a lot depends on what’s included or excluded in the definition of public debt.

The State Bank of Pakistan’s (SBP) bulletin shows that the ratio using “total debt and liabilities” was 100.3pc versus 74.9pc using “total debt of the government” under the Fiscal Responsibility and Debt Limitation Act, 2005.

More telling are numbers on debt servicing.

Interest on loans is the single largest expense in the federal budget 2020-21, greater than “defence affairs and services” and also greater than the whole of “development expenditure”.

How does Pakistan compare in South Asia?

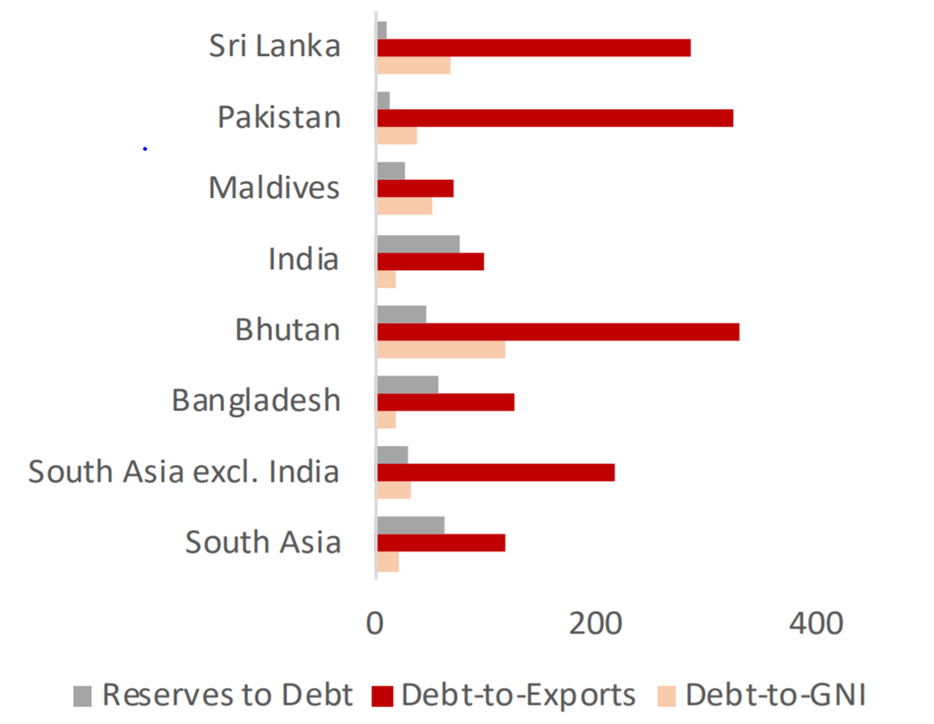

The World Bank’s Debt Report 2021 Edition I provides a useful bar chart, which is reproduced below, comparing the debt of South Asian countries using data for the end 2019.

Because of the high debt-to-exports ratio, the scale in the graph goes up to 400pc. The chart shows that Pakistan is lagging behind India and Bangladesh and bears some similarities with Sri Lanka.

Sri Lanka, which now has a credit rating worse than that of Pakistan, helps illustrate the perils of debt.

In 2017, struggling to repay its debts, it signed a 99-year lease with a state-run Chinese company on a port and about 15,000 acres nearby for an industrial zone, an arrangement that has become known as the “port deal”.

This is a useful international precedent to dispel the myth that relief, forgiveness, or default could be a solution for Pakistan’s debt.

According to a set of 2020 data on public finance, among countries with the debt-to-GDP ratio exceeding 80pc, Pakistan’s interest-to-revenue ratio is the second-highest after that of Sri Lanka.

However, if Pakistan’s interest-to-revenue ratio from the federal budget is calculated using the revenue net of the provincial share, it comes out at just about 80pc, even greater than that of Sri Lanka.

What’s the view of the IMF?

Influential multilateral lenders the IMF and World Bank have jointly developed a debt sustainability framework.

It defines debt sustainability as follows: “In general terms, public debt can be regarded as sustainable when the primary balance needed to at least stabilise debt under both the baseline and realistic shock scenarios is economically and politically feasible, such that the level of debt is consistent with an acceptably low rollover risk and with preserving potential growth at a satisfactory level.”

The definition is quite a mouthful and it is unclear what exactly is meant by “politically feasible”, “acceptably low”, “satisfactory”, etc.

Centered on the excess of government’s revenue over expenditure other than interest, it is in effect a description of the process used under the debt sustainability framework.

There is a lot of judgement involved and using the same framework and data, different analysts may reach different conclusions.

According to the IMF’s report on Pakistan dated April 8, its debt sustainability analysis confirms that “public debt remains sustainable with strong policies, but also points to risks from policy slippages and contingent liabilities”.

What do the credit rating agencies say?

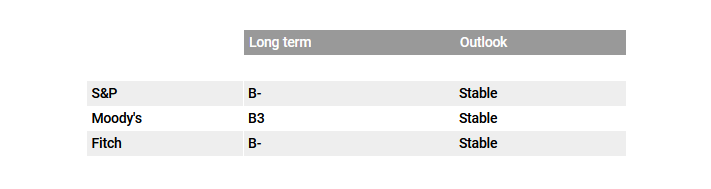

A credit rating is meant to be an independent opinion on the ability and willingness of a country to pay back its debt in full and on time. The three influential rating agencies — S&P Global, Moody’s, and Fitch Ratings — have rated Pakistan at the lower end of the highly speculative grade.

Since Pakistan started to get rated in the 1990s, our credit rating has moved within and across highly speculative and substantial risk categories and in 1998-99, following the nuclear tests, Pakistan has been deemed a defaulter.

The S&P, the largest rating agency, says that its sovereign ratings reflect its “analysis of institutional and governance effectiveness, economic structure and growth prospects, external finances, and fiscal and monetary flexibility”.

According to a research paper on which factors determine sovereign credit rating, these are “mostly influenced by per capita income, government income, real exchange rate changes, inflation rate and default history”.

What do independent entities and researchers think?

Let’s now take a look at views of some of the independent entities and researchers.

Jubilee Debt Campaign, an influential voice on debt, is a UK-based charity “focused on the connections between poverty and debt”.

It identifies Pakistan as one of the 52 countries facing a debt crisis. It defines a debt crisis “where debt is leading to human rights being denied, or even being put ahead of life itself”.

The Institute for Policy Reforms (IPR), a Lahore based research entity, contends in a report published in April that the “most critical problem faced by the Pakistan economy is repayment and servicing of external debt” and that instead of bringing economic growth, “borrowing creates more borrowing with an external account crisis waiting to happen”.

In a 2020 literature review on debt and economic growth covering 24 studies published over a decade, two researchers from George Mason University contend: “The empirical evidence overwhelmingly supports the view that a large amount of government debt has a negative impact on economic growth potential, and in many cases that impact gets more pronounced as debt increases.”

What about the Fiscal Responsibility and Debt Limitation Act, 2005?

The purpose of the act is to provide for reduction of the federal fiscal deficit and ratio of public debt to gross domestic product to a prudent level by effective public debt management and covers both fiscal responsibility and debt limitation.

The act required that the debt-to-GDP ratio to be reduced to 60pc by the end of 2017-18 and then gradually down to 50pc by 2032-33.

It wasn’t a wish or a plan, it was the law. However, over the years, we did not follow it.

Sustainable at whose cost?

To be fair, it is difficult to define a multi-faceted concept like debt sustainability and there are no either-this-or-that rules.

Having said that, there is a stark difference between the views of the IMF and credit rating agencies on one hand and those of Jubilee and IPR on the other.

A key reason that explains the difference is that the former see debt sustainability from the eyes of the lenders that are concerned with repayment, while the latter see it from the eyes of those who have to pay it — the people at large who are concerned with their welfare.

Pakistan’s debt would have helped us if it were invested to build the productive capacity of our economy, generating returns greater than the interest rate and earning forex through growing exports. But the fact that we are taking on more debt to manage previous debt and our exports-to-GDP ratio has declined shows that surely has not been the case.

The high degree of indebtedness has made Pakistan more vulnerable to economic shocks and weakened us politically vis-a-vis our powerful external lenders. It has also greatly reduced our ability to do what we need to do, for example, invest in education and healthcare.

Let’s remind ourselves that on the human development index Pakistan’s rank (154) is worse than that of India (131), Bangladesh (133), and Sri Lanka (72).

We need higher economic growth to alleviate poverty but again it is our debt that stands in the way.

Because the discussion about public debt is often laden with economic jargon and numbers running in trillions, it appears too abstract and complex to be relevant to our day-to-day life.

We are likely to see inflation and unemployment as our main problems, which we can better understand and feel. But in the process, we overlook how deficit and debt fuel inflation and unemployment for reasons such as inability to invest in our people and currency depreciation.

The cost of debt repayment is largely spread over the majority that has little ability to pay.

For example, more than 60pc of the revenue collected by the Federal Bureau of Revenue (FBR) is indirect, such as the taxes on petroleum products.

If Pakistan’s debt is sustainable, it is only so at a great human cost.

Can Pakistan reduce its public debt?

The good news is that yes, public debt relative to the size of our economy can be and has been reduced.

Two economists studied 206 debt reductions using a data set for 160 countries for 1970 to 2009 where the debt-to-GDP ratio declined by at least 15 percentage points over five consecutive years.

The results of their study show that “a large debt reduction is associated with robust economic growth, decisive and lasting fiscal consolidation, and a favorable external environment characterised by strong global growth”.

The IMF baseline projections for Pakistan in its April report include a large reduction in tax-to-GDP ratio from 92.9pc in 2021 to 69.2pc in 2024.

Pakistan has experienced a falling debt-to-GDP ratio in the decade of 2000. It fell from above 80pc to below 60pc for reasons such as forex inflows in the aftermath of 9/11 and economic growth.

There is no secret to what needs to be done to cut deficit and debt: broaden tax base for direct taxes, cut unnecessary expenses and subsidies, invest in export-led economic growth, increase remittances, shift to more efficient ways of raising longer-term debt, build institutional capacity to manage debt, and so on.

The bad news is that cutting the deficit and debt requires us to succeed where we have failed in the past. For example, our tax-to-GDP ratio has moved between 9pc to13pc whereas its potential is estimated at about 22pc.

Tax authorities must now make use of the data and the analytical tools to track down those evading direct taxes, such as those in the real estate sector.

To sum up, when it comes to threats to Pakistan, many point to fifth generation warfare whereas it is public debt that is slowly but surely bringing the country to its knees.

There is nothing to be gained by political point-scoring or blaming anyone for not offering a magic solution to a mega problem.

Instead, it’s about time we came together to sort out our debt — or else it will continue to sort us out.