By Dr Abid Qaiyum Suleri

Published in The News on December 10, 2023

The Covid-19 pandemic, a phenomenon that eluded previous infectious threats like Ebola, SARS, MERS and swine flu, was declared a pandemic not only due to its contagious nature but also because it posed a threat to humanity, transcending wealth, nationality and religion. Similarly, climate change, with its devastating impacts like rising sea levels, intensified hurricanes, extreme rainfall and prolonged droughts, has made the entire world vulnerable, regardless of the development stage, national boundaries, or any other fissure that divides humanity. That is why the annual Conference of Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change has gained significance.

In the case of Covid-19, those with robust immunity fared better, mirroring how resource-rich nations are better equipped to tackle climate change. UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres aptly says that our planet has passed the stage of “global warming” and entered into what he terms a “global boiling,” where the affluent nations can mitigate the effects while lower-income countries face the brunt due to limited resources and unpreparedness.

There is a crucial distinction emerges between Covid-19 and climate change: the very nations capable of combating climate change are often the culprits behind increased greenhouse gas emissions causing the global boiling. For instance, developed countries’ extensive use of fossil fuels, historically and currently, has significantly contributed to the heightened concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

Our Earth operates in a timeless cycle of life, where resources are constantly depleted and replenished, emphasising the delicate balance supporting all forms of life. However, human activities, particularly in developed nations, have disrupted this balance, leading to a myriad of ecological crises.

For years, some developed nations, notably the USA, have denied their role in upsetting the natural balance of atmospheric gases. The USA did not ratify the Kyoto Protocol (which came into force in 2005) that had made it mandatory for industrialised nations to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions. This is one of the reasons was that the Kyoto Protocol exempted developing countries and emerging economies from such mandatory emission reduction. This was a major source of tension between the developed and the developing countries in multilateral climate negotiations.

The phenomenon of “common responsibility is no one’s responsibility” persisted until 2015 when scientific evidence confirmed that human activities were the primary driver of climate change. The Paris Agreement emerged during COP21. It involved 196 countries committing to National Determined Contributions (NDCs) to limit the global temperature rise to well below 2 °C (3.6 °F) above pre-industrial levels, and preferably limit the increase to 1.5 °C (2.7 °F), recognising that this will substantially reduce the effects of climate change.

Unlike the Kyoto Protocol (signed by 84 countries), the Paris Agreement engaged all nations, rich and poor, in emission reduction efforts. Developed countries pledged to mobilize $100 billion annually by 2020 to help developing nations implement their NDCs, based on principles of equity, transparency and accountability. The excitement of COP21 waned with the US withdrawal from the Paris Agreement under the Trump administration. However, the USA rejoined in January 2021 under the Biden Administration.

COP26 in 2021, held in Glasgow, witnessed a push to phase out fossil fuels to curb global temperature rise, despite resistance from major producers (Saudi Arabia) and major consumers (China and India). South Africa was provided “transit financing” by a group of developed nations to phase out its coal-powered plants.

COP27 in 2022, held in Sharm-el-Sheikh, showcased Pakistan’s exemplary leadership as the president of G77 plus China. In the aftermath of Pakistan’s super floods, Senator Sherry Rahman, the then climate change minister, successfully advocated for a loss and damage fund. The announcement of L&DF addressed the unmet demands of vulnerable developing countries since 1991.

This fund aligns with the principles of common but differentiated responsibilities, acknowledging developed countries’ historical obligation to support developing nations affected by climate change. It emphasises equity and justice, recognising the right of developing countries to compensation and participation in the fund’s governance.

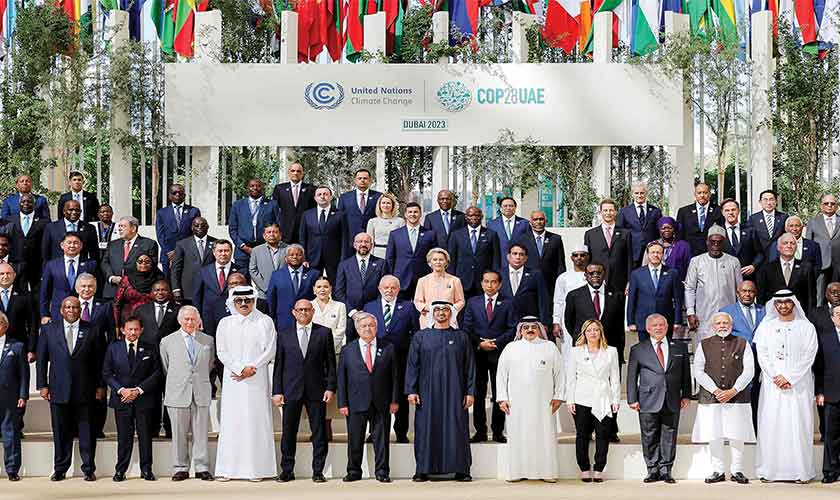

The agenda of COP28, the current iteration ongoing in the UAE since November 30, is intricately shaped by negotiations carried forward from the preceding 27 COPs. The pivotal issues under discussion in COP28 encompass reviewing progress towards achieving the Paris Agreement goals, enhancing adaptation and resilience to climate change impacts, mobilising financial resources for developing countries to address climate change, deliberating over fossil fuel phasing out versus phasing down, and addressing loss and damage associated with climate change impacts (operationalisation of the L&DF).

In essence, the overarching agenda boils down to bridging the gap between the developing world’s demands for corrective actions by the developed world, addressing past and present mistakes in disrupting the natural balance and what the developed world has committed to doing.

Encouragingly, developing countries achieved a significant milestone in making the Loss and Damage Fund operational. However, this success came with concessions on the fund’s host (the World Bank, at least for the interim period), the fund amount (remaining below $1 billion, a figure dwarfed when compared to global losses and damages) and the funding source (an issue of pledges potentially being duplicated).

Regarding stock taking, post-Paris Agreement, positive strides include the rise in renewable energy capacity (from 230 gigawatts in 2015 to 1,050 gigawatts in recent years) and the adoption of carbon-pricing schemes. Despite these advancements, even with course corrections, global warming is projected to hover around 2.5-2.9°C—above the intended target and still posing significant risks to billions, especially in the developing world.

NCQG is currently under discussion, necessitating a credible process to prevent double accounting and ensure additional funding. COP28 is anticipated to kickstart discussion on a new NCQG considering the needs and priorities of developing countries. However, substantial progress is not expected until COP29.

The dream of fossil fuel phasing out faces challenges. The president of COP28, also the president of the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company, initially made a statement (later clarified as misreported by the media) asserting no scientific evidence supporting fossil fuel phase-out to contain global warming. Additionally, Saudi Arabia has threatened to veto any text advocating the phasing out of fuel, suggesting a potential agreement on fossil fuel “emission” phase-out using not yet commercially viable carbon removal methods.

By early next week, the complete text of the agreement among the 200 participating parties will be unveiled. Regardless of the current COP28 output, the COP process, is akin to the UN Security Council or the Indus Basin Treaty. They may not always yield immediate positive changes in our lives. Still, their absence could have huge detrimental effects. Hence, adhering to the process remains crucial unless an alternative garnering consensus from all 200 countries emerges.