By Shahid Yusuf

Published in center for Global Development on June 16, 2021

Among South Asian economies, Bangladesh is touted as a rising star. In 2019, its per capita income was $1,856—substantially higher than Pakistan’s $1,285 and only $250 less than that of India. In 2020, Bangladesh might have edged ahead of India because it registered a growth rate of 2.4 percent whereas India’s GDP shrank by 7.3 percent. These numbers—especially the positive rate of growth during the pandemic year—are striking, part of an impressive growth performance that has averaged close to 6 percent per annum since the turn of the century (Figure 1) (although questions have been raised as to whether the GDP data accurately represents Bangladesh’s economic performance). Few least developed countries can match Bangladesh’s record in this respect. Various indicators of human development also show significant improvement: life expectancy in 2019 was 72.6 years, a gain of over 7 years since 2000; mean years of schooling were up from 4.1 to 6.2; and the country’s human development index (HDI) value had climbed from 0.478 in 2000 to 0.632 in 2019. Bangladesh’s HDI ranking is now 133rd out of a total of 189 countries, still relatively low but better than both Pakistan (154) and Nepal (142).

Figure 1. Bangladesh GDP growth

Source: World Development Indicators (2021) https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG?end=2019&locations=BD&start=2000

On reviewing Bangladesh’s achievements on its 50th anniversary, Kaushik Basu maintains that “Bangladesh’s remarkable economic transformation—the World Bank now classifies it as a lower-middle-income economy—deserves praise and can offer important lessons for today’s low-income countries.” But is the praise entirely justified? Can Bangladesh now serve as a model for other countries, perhaps offering an alternative to the longstanding East Asian export-led growth paradigm? The jury is still out however, and the evidence raises doubt that the East Asian icons face serious competition from Bangladesh—at least not yet.

The sources of growth

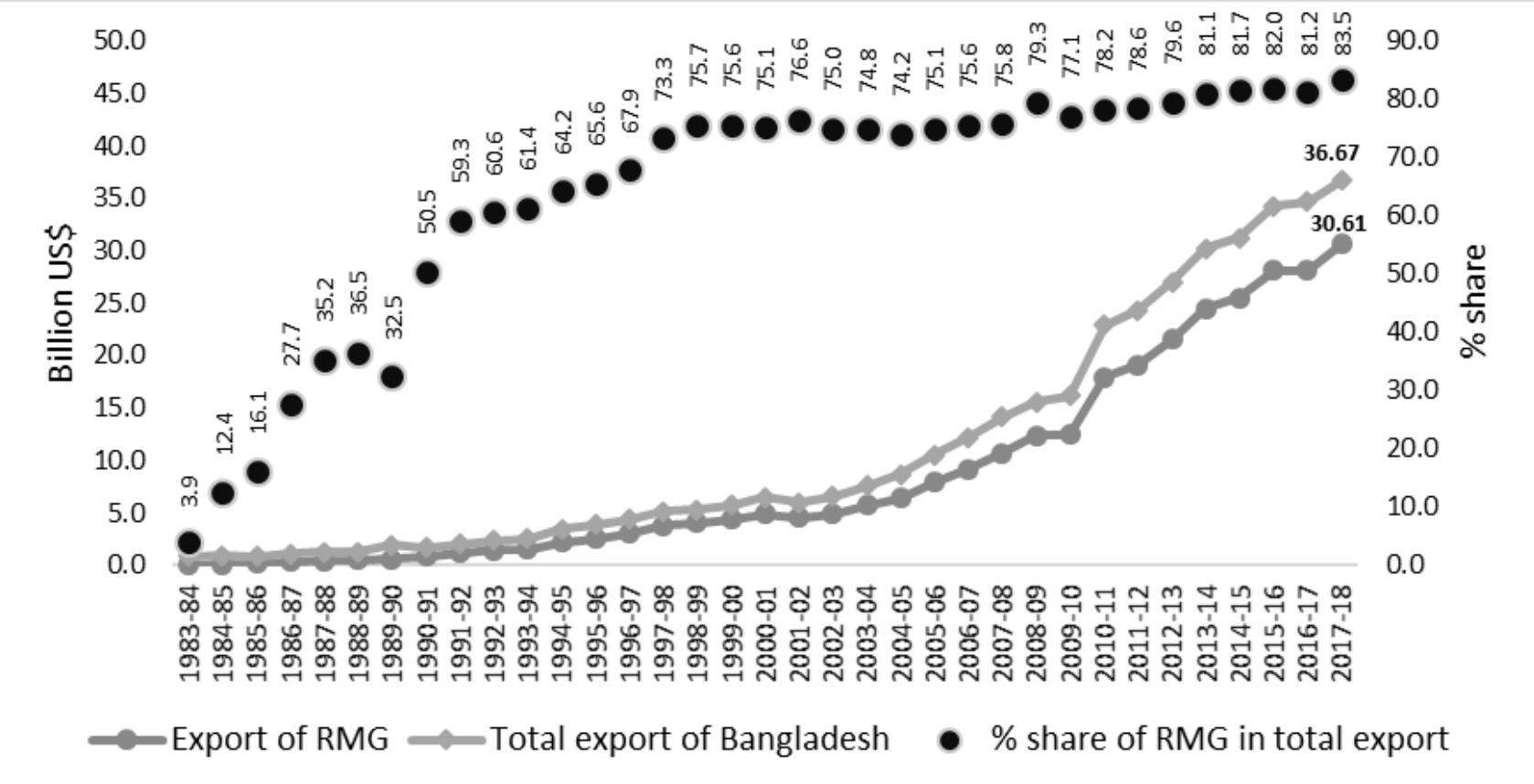

Bangladesh’s growth stems in large part from its success as an exporter of garments, which account for 84 percent of its total exports, and remittances from overseas, which amount to over 6 percent of GDP (Figure 2). The principal driver of growth is investment, which has risen from 24 percent of GDP in 2000 to 32 percent in 2019. Very little is derived from total factor productivity—below 1 percent per annum since 2000—the primary determinant of long-term growth of incomes for all countries. To paraphrase Paul Krugman, it is perspiration, not inspiration, that is responsible for Bangladesh’s performance to date.

Figure 2. Bangladesh: Exports of garments and total exports

Source: S. Raihan and S.S. Khan (2020) Structural transformation, inequality dynamics and inclusive growth in Bangladesh. WIDER Working Paper 2020/44. https://www.wider.unu.edu/sites/default/files/Publications/Working-paper/PDF/wp2020-44.pdf

Is it sustainable?

A closer look raises other questions over the quality of this economic record.

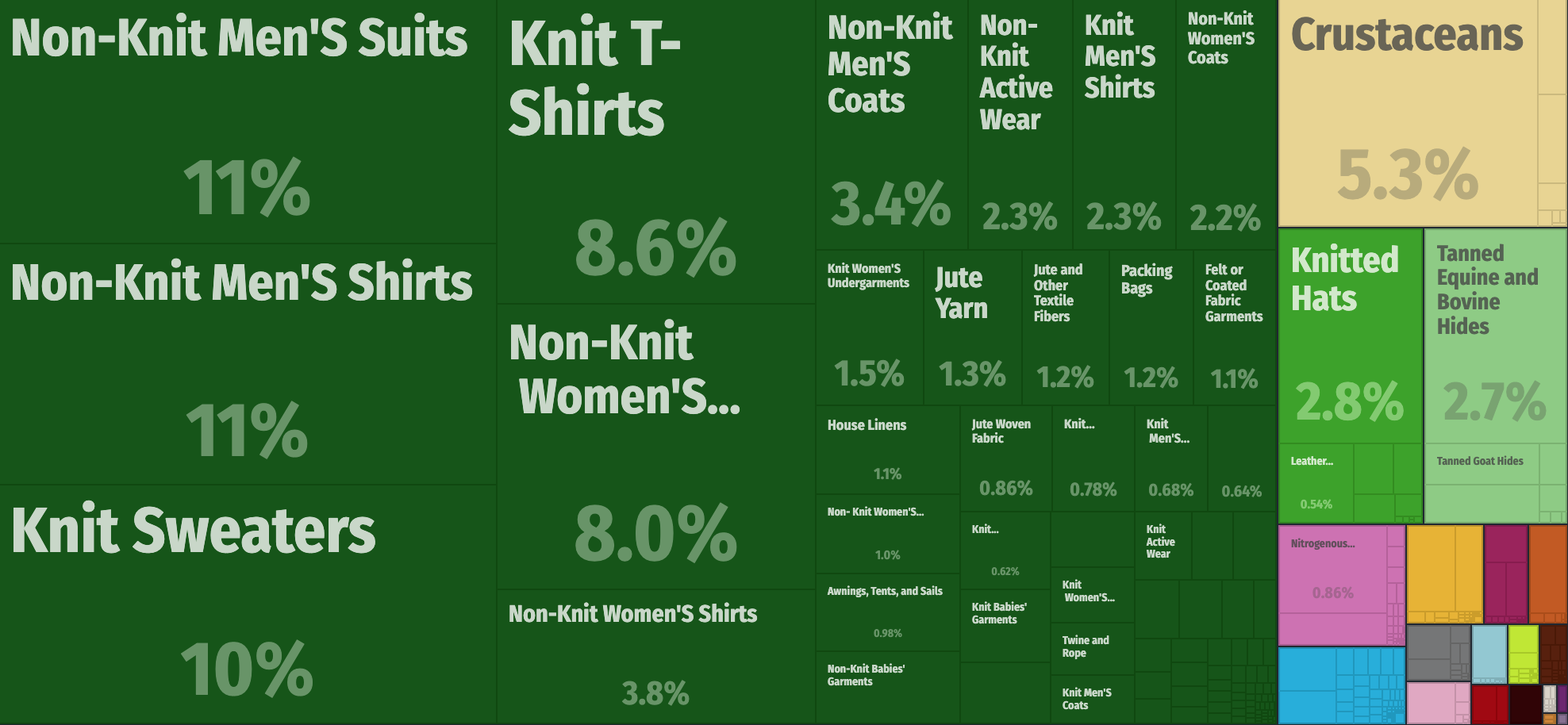

First is the extreme dependence on a single category of exports (SITC 841-846) and the low share of exports to GDP. Whereas a country like South Korea managed to diversify away from resource-based products, garments and footwear within a matter of fifteen to twenty years—starting in 1963—and emerged stronger as an exporter of complex products including steel, machinery, chemicals, transport equipment, and consumer electronics, Bangladesh remains focused on a narrow range of relatively low-value garments more than forty years after the industry took root in 1977-1982, following investment by Korea’s Daewoo in Desh Garments and denationalization of the textile industry (Figures 3&4). T-shirts, trousers, sweaters, and shirts remain the dominant export items and 80 percent of exports were to the relatively slow-growing markets in the European Union and the United States. Although Bangladesh has attempted to diversify into pharmaceuticals and can meet most of domestic demand, export earnings were a mere $130 million in 2019.

Second is the falling share of exports in GDP, which fell to 15 percent in 2019 from a peak of 20 percent in 2012, far short of Vietnam’s ratio of 107 percent (Figure 5). In addition, the economic complexity of Bangladesh’s trade has also slipped (that ranking is down from 77 in 1991 to 123 in 2017).

Third, needed diversification is slowed by the weakness of private investment in new industries, which has been exacerbated by constraints on the availability of credit, especially to small and medium enterprises. The entry and growth of firms is also hampered by the deterioration of the business environment: Bangladesh was ranked 65th of 155 countries in 2006 in the World Bank’s Doing Business index. By 2020, it was in 168th place of 190 countries. Bangladesh was ranked 105th by the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Index for 2019, down two places from 2018.

Figure 3. Bangladesh export composition, 2017

Figure 4. Bangladesh export composition, 2000

Source: OEC: https://legacy.oec.world/en/visualize/tree_map/hs92/export/bgd/all/show/2017/

Figure 5. Exports as a percentage of GDP: Bangladesh vs. Vietnam

Source: WDI (2021) https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NE.EXP.GNFS.ZS?locations=BD-VN

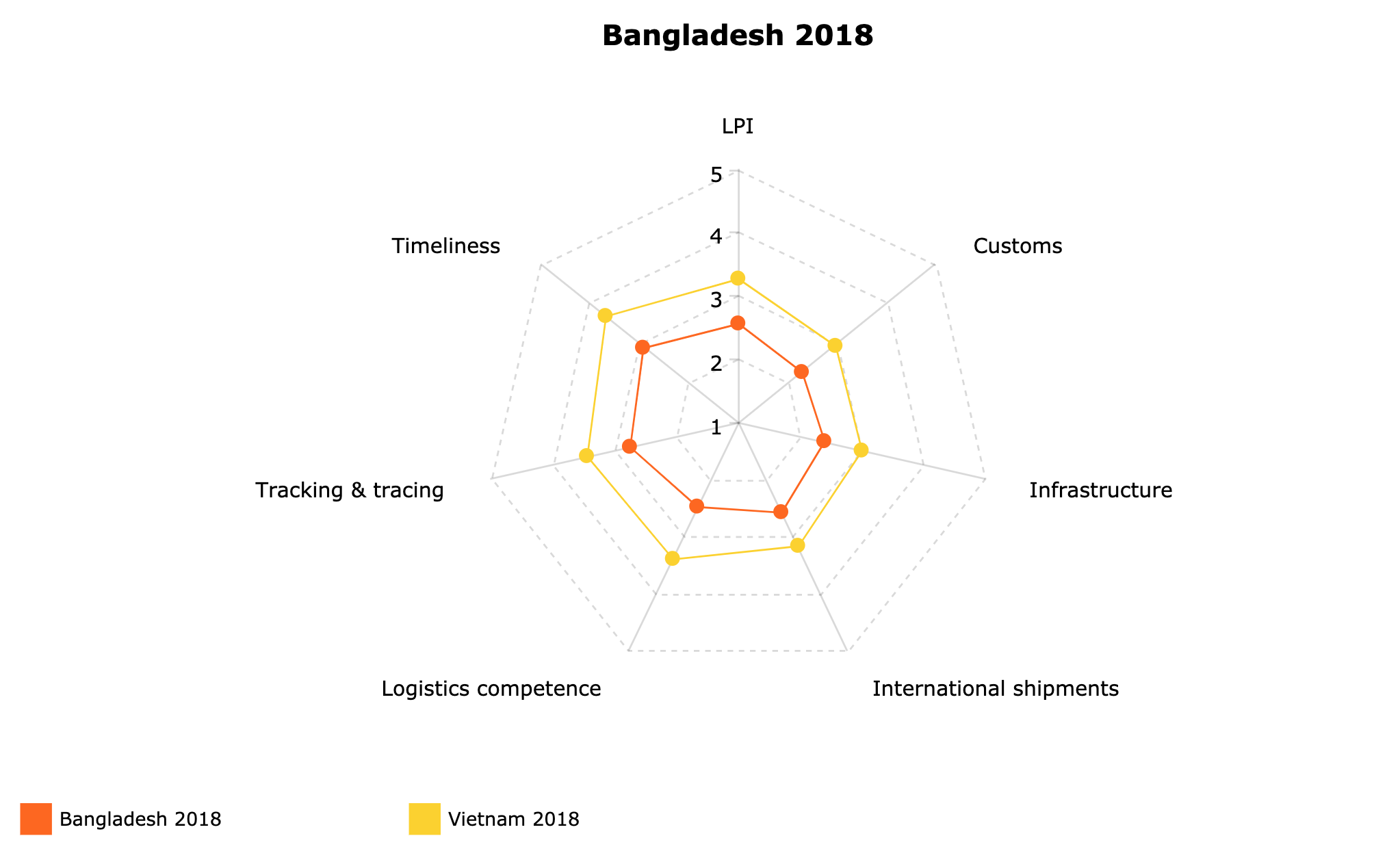

Other indicators underscore the risk that Bangladesh is heading towards a (lower) middle-income trap, notwithstanding its recent growth performance. It remains a relatively closed economy with tariff barriers that are above the already high South Asian average and almost twice the average for lower-middle-income countries. Hence, development is increasingly inward-looking with firms turning to rent-seeking activities. Bangladesh is ranked low on the World Bank’s Logistics Performance Indicator (LPI), which has a bearing on a nations’ export prospects. It slid to 100th place in 2018 while a competitor, Vietnam, ranked 39th and scored higher on every sub sub-indicator (Figure 6). Exporters and importers face transactions cost much higher than those impinging upon competitors in Southeast Asia. Their woes are compounded by the unreliability of electric power, in spite of private investment in generating capacity, because transmission and distribution infrastructures have been neglected. Corruption is pervasive, reflected in Transparency International’s ranking: In 2020, Bangladesh had the dubious distinction of occupying the 146th slot between Angola and the Central African Republic, a drop of three places from 2010.

Figure 6. Bangladesh vs. Vietnam on the World Bank’s Logistic Performance Indicator (LPI) scale

Source: https://lpi.worldbank.org/international/scorecard/radar/254/C/BGD/2018/C/VNM/2018#chartarea

It is no surprise that the country has not proven attractive to foreign investors. Bangladeshi firms are price-competitive however, as a recent World Bank report notes (on page 12), “[They] perform poorly in the areas of compliance, quality, and reliability—which are important in attracting foreign investment.” Foreign direct investment (FDI) has averaged just 1 percent of GDP over the past two decades and the FDI stock in 2020 was only equal to 6 percent of GDP—far below the level of other countries in the same income category. Consequently, there are no major anchor multinationals that can facilitate diversification, help seed a cluster of local suppliers, and enable integration with value chains for electronics or auto parts. The experience of Vietnam, which has attracted investment in the electronics industry from Japanese and Korean multinational corporations, and of Thailand, which the major auto manufacturers have made into the Detroit of Southeast Asia, is not being replicated. Samsung is not assembling smartphones in Bangladesh nor do Japanese auto manufacturers view the country as a future hub for auto parts.

Strong headwinds

With 50 million people (close to 30 percent of the population) living in poverty in 2020, income inequality on the rise (the Gini coefficient rose from 0.458 in 2010 to 0.482 in 2016, and The Economist notes that incomes of the richest households rose by a quarter while those of the poorest fell by a third), two million young jobseekers entering the labor market each year for the next decade, and climate change posing formidable risks (it is ranked as the 7th most vulnerable country), Bangladesh faces severe challenges. It enjoys growth momentum, but its fortunes are much too closely tied to a single, low-tech industry and to overseas remittances. The failure to use garments as a springboard to diversify into more complex products, as Korea did; to nurture world class firms with brand recognition, as several East Asian economies have done; to improve the business environment and governance; and to raise factor productivity, which determines whether a country moves steadily up the income ladder, warn of troubles ahead.

Are there lessons from Bangladesh?

Are there any lessons to be drawn from the Bangladesh story for other late-starting least developed countries (LDCs)? Five come to mind.

One is that countries can climb the first one or two rungs of the development ladder if they can establish a large, cost-competitive garments industry and integrate with the global value chain (GVC). Scale definitely matters. Bangladesh had 4,600 factories producing garments in 2019 and exports amounted to over $33 billion. However, any new entrant must compete with the likes of established producers such as Bangladesh, Vietnam, Cambodia, Pakistan, and Ethiopia, not to mention China and Turkey. Integrating with the apparel GVC and achieving scale has become a lot harder and with automation, the advantages of low-cost labor are less compelling.

Second, the experience of Korea and other East Asian economies demonstrated the need for early diversification into higher-value manufacturers. All these countries began their ascent up the income ladder by producing light manufactures but then quickly branched out into complex products. In the Hausman-Hidalgo-Klinger terminology, these “monkeys” moved from one end of the forest to the other in one big leap. That sort of structural transformation now looks forbiddingly difficult for an LDC, even Bangladesh. There are technological barriers to entry, high-value GVCs are harder to integrate with for newcomers, manufacturing is automating and becoming servitized, and the share of manufacturing in GDP and its contribution to growth is diminishing. As we can see from the Bangladeshi case, the Korea/Taiwan-type manufacturing and export-led growth stories are not being replicated—not by Bangladesh, or emerging markets such as India, Brazil, and Mexico.

Third, Vietnam, the only country that appears to be following the East Asian playbook, highlights the importance of foreign direct investment (FDI) in firmly placing a country on the path to rapid and sustainable growth. It would seem highly desirable for countries that are ambitious and entrepreneurial to pull out the stops—fiscal and otherwise—to attract FDI that could accelerate the process of diversification. The Singapores and Irelands of the world would never have made it without a high volume of FDI.

Fourth, homegrown, high-growth conglomerates can complement the push administered by multinational corporations. Korean chaebol carpentered the Korean miracle, Taiwanese contract manufacturers have undergirded its prosperity, and Vietnamese conglomerates are contributing to industrial diversification.

Last but not least, the only sure way to escape from the lower-middle-income trap is to by raising factor productivity year after year. In addition to the above measures, countries need to improve the quality of human capital. Years of schooling without much learning do not suffice. A deepening of technical and managerial skills would enhance the productivity gains from digital technology. Moreover, private entrepreneurship and investment are inseparable from growth that is productivity-led. This is more likely to be forthcoming where there is stable and predictable policy environment, a firm commitment to openness and to growth, and where the grasping hand of the state is credibly checked by political and legal institutions. Creating what Acemoglu and Robinson call a “narrow corridor” has not been easy for LDCs, including Bangladesh, but arguably such a corridor that balances the tensions between state and society, is more likely to lead to the rapid and sustainable growth that would allow Bangladesh to become a true growth miracle.