Published in Dawn on June 19, 2023

“No one puts their children in a boat unless the water is safer than the land” —

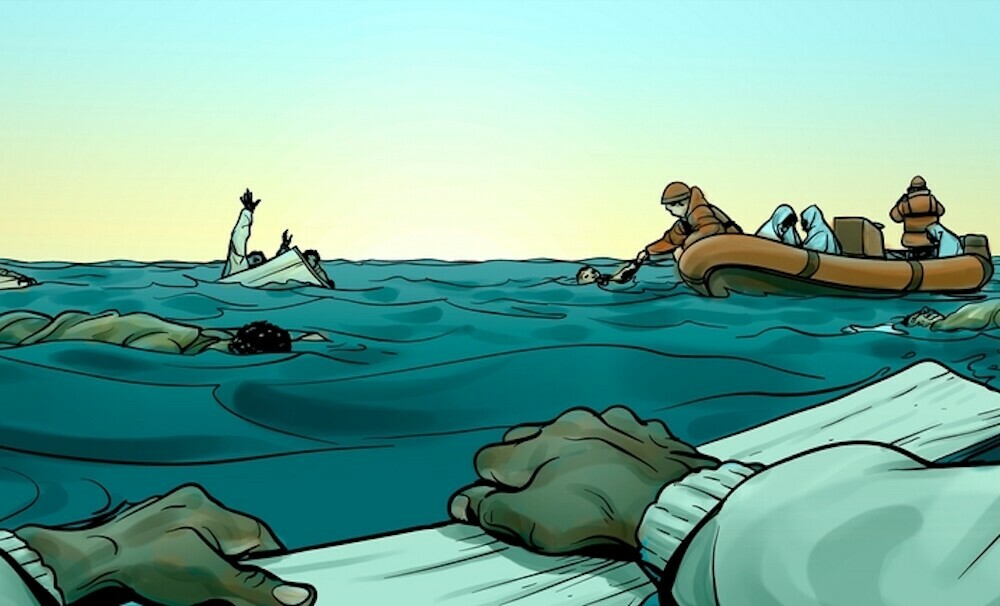

Last week, against all odds, around 750 refugees, including 400 Pakistanis, set off on a trawler destined for Italy from Egypt in search of a better future. Three days later, the engine failed, the boat capsized and all but 79, including 12 Pakistanis, lost their lives off the coast of Greece. According to reports, Pakistanis were kept below deck, where chances of survival are even more grim if a boat capsizes.

With over 500 people still missing, the survivors have shared harrowing details of what is now shaping to be the deadliest shipwreck off the coast of Greece this year.

Week after week, desperate stories such as this are reported in the press around the world. You would, thus, be forgiven for thinking that governments would join hands in search of a humane solution.

But don’t hold your breath.

Inhumane policies

“Stop the boats” is the latest migration policy of the Conservative government in the United Kingdom. It’s the slogan of choice for a new bill that aims to discourage migrants from arriving in the UK illegally by denying them certain basic protections.

The slogan aptly represents the bill — both abhorrent and derogatory in equal measure. It states that people who have entered the UK illegally have to be deported. They also lose any legal protection that they would have otherwise received, even if they are victims of human trafficking and modern slavery. This effectively means that if you are a victim of human trafficking and land up in the UK, the law will not protect you, but rather release you back into the hands of the traffickers.

This is not a one-off. Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni once said: “Repatriate migrants and sink the boats that rescued them.” After coming to power and fuelling her campaign with anti-migration promises, the Italian government has recently passed a law that prevents search-and-rescue ships from looking for migrant boats in distress.

Fiercely debated in Europe, the ripples of these efforts will be felt thousands of miles away in countries all over the world. In the recent past, tragic stories in the Pakistani press manifest the critical need to treat refugees and migrants with empathy and fairness.

‘You only leave home, when home won’t let you stay’

Shahida Raza was a single mother and professional hockey player. After having represented Pakistan as well as other departmental teams, she lost her job when departments began to cut costs. She ran from pillar to post seeking employment, which would have enabled her to get medical treatment for her son.

As her hopes slowly dwindled, Raza was forced to take a leap of faith and decided to attempt the treacherous journey to Europe for the sake of her child’s future. Four months after her departure, news reached Pakistan that a boat carrying migrants had crashed against rocks and sank in the southern Italian coast. Raza was one of the 28 Pakistanis who didn’t survive.

On the same night that the seas took Raza’s life, seven Pakistanis set aboard another boat destined for Italy from Libya. This boat met its tragic fate off the coast of Benghazi and all of them also lost their lives.

Despite being clearly laced with peril, more Pakistanis (among others) set off on boats from Libya to Italy in April. Before long, news filtered through that the bodies of 57 of these passengers had been washed ashore in Libyan coastal towns. One of the survivors, Bassam Mahmoud from Egypt, described how one of the inflatable vessels carrying 80 migrants set off in the middle of the night, raising concerns from passengers about the safety of the boat, but “the man in charge refused to stop,” he said.

Week after week, as governments in Europe look to tighten the screws on their policies, the determination of migrants to risk their lives on precarious boats only seems to be increasing. But with that, so is the number of lives lost.

Same story, different subjects

This isn’t a new phenomenon. In the aftermath of the two world wars, millions of people were forced to leave their homelands in search of new lives in foreign countries.There was thus a desperate need to regulate the refugee system.

Negotiations between Western powers started with the League of Nations in 1921 and eventually gave birth to the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees — or the 1951 Refugee convention — 30 years later.

The convention defines refugees as someone who is “unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion.” Importantly, the convention clarifies that subject to specific exceptions, refugees should not be penalised for their illegal entry or stay in a country. This recognises that in order to seek asylum, refugees may end up breaching immigration rules.

Moreover, the convention requires host countries to give migrants employment opportunities, housing (subject to control by public authorities), public education and even a share in rationing if the need arises. It also codifies the principle of non-refoulement. This means that a refugee cannot be expelled or returned to a country where they face threats to their life and freedom.

But that is precisely what seems to be happening today. In 2022, the UK government introduced a scheme through which illegal immigrants and asylum seekers would be relocated to Rwanda. And now, the new bill also states that illegal migrants must be deported.

European governments contend that these measures are necessary to curb illegal immigration. Italian officials claim that the migrant crisis has reached unsustainable levels and is threatening infrastructure. The UNHCR, the United Nations refugee agency, estimates that over 100,000 people arrived in Italy by boat in 2022 alone. This is despite the fact that more than 50,000 people have died attempting to reach safer shores since 2014.

No one denies there is a serious problem. The difference arises in the search for a solution. Does it lie in offering safe shores or the mouth of a shark?

The irony is that when the world was faced with a refugee crisis in the last century, governments joined hands to protect refugees by entering into the Refugee Convention. This time too, governments are passing laws — just of another variety. While the objective then was to protect and promote fundamental human rights, the objective now is to prevent them.

Let me leave you with an image that shook the world. It’s from 2015. A lifeless three-year-old boy in a red T-shirt and blue shorts lying head down on a beach in Turkey. He was on a boat trying to flee his homeland after a civil war broke out between insurgents and Kurdish forces. By that time, approximately 250,000 had been killed in Syria and millions had been displaced. What choice did he have?