By Shazia Mehboob

Published in The Express Tribune on February 16, 2022

ISLAMABAD: Pakistan’s constitution makes no distinction between genders but women in parliament know that’s not the reality in politics. Despite impressive records of women in the legislative assembly, female parliamentarians still face barriers to entry that their male colleagues don’t — keeping many women, save for a few with family members in politics, out of these positions.

The current makeup of Pakistan’s parliament is only 21 percent female. In the National Assembly, which consists of 342 members, female representation is only around 3 percent if reserved seats are excluded; There are 60 seats reserved for women. These numbers are emblematic of a male-dominated political culture which — along with other socio-economic factors — creates a glass ceiling for women’s political advancement.

Mukhtar Ahmed Ali, the Executive Director for the Centre for Peace and Development Initiatives (CPDI), said the system of indirect elections (political parties awarding seats through nepotism instead of merit) is one contributing problem. He says a political culture of allotting party tickets to women in constituencies where chances of winning are low also creates a barrier to entry.

Big names like Fatima Jinnah, Benazir Bhutto and the Kulsoom Nawaz helped establish a strong foundation for the acceptance of female leaders in Pakistan, but there are still obstacles for women who want to participate in public politics. Legislative reforms have tried to address these problems of representation, but progress has come in fits and starts.

From 1977 to 2008, the percentage of women in parliament increased gradually after advances for women put in place by the administration of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto. Under former president Pervez Musharraf, the assemblies reserved 60 seats for women, prompting an encouraging uptick in the number of women candidates elected. The Election Act of 2017 criminalized any effort to hinder women’s participation in elections. The act also required political parties to have a minimum of 5 percent of their candidates contesting for general seats be women.

One year after the act passed, Pakistan saw a record-breaking number of women candidates run for seats in the National Assembly. However, only eight out of 183 women contestants won. That same year, all mainstream political parties kept close to the minimum percentage of female candidates, while almost half of Pakistan’s political parties did not field any female candidates. Many women candidates were given tickets in constituencies where the party had little or no chance of winning. Some of these candidates did not partake in formal campaigns for elections in these areas.

According to data from the Inter-Parliamentary Union, a global organization of international parliaments, representation of women in parliament has varied since 1947, but since 2002, neither constitutional amendments nor structural reforms have increased women’s representation writ large.

Bittersweet progress

Despite the persistence of skewed gender ratios in parliament, Pakistani women continue to persevere in politics — facing off against male competitors in areas where patriarchy rules supreme. However, wins in these areas often highlight the complicated social and familial factors that can dictate how political campaigns for women look.

One recent example from Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa shows progress for women in politics while highlighting how much work Pakistan still needs to do to achieve equal representation for women in parliament. The local government election took place in 17 districts in KPK and made history as women from highly conservative constituencies contested and won general seats in addition to reserved ones.

According to data from the Election Committee of Pakistan, there were a record number of women contesting local government elections in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa in December 2021. More than 35,700 candidates ran in tehsil, village, and neighborhood councils in the local body elections in KP of which 3,900 were women. During the first phase of the elections, 4,214 female candidates ran for 2,383 seats. In the three tribal districts, there were a total of 591 women candidates.

Still, practical politics (public campaigning) was restricted for women taking part in these elections.. During the election, Zainab Bibi and Kulsoom Bibi, residents of Plodhir Village Council-1 in Mardan, both won seats – one on a reserved seat and one on a general seat. However, campaign matters were handled by their husband (he is married to both women). Additionally, neither of the women’s details were mentioned on their election banners or pamphlets. Instead, these promotion materials shared the details of their husband.

This example reflects Pakistan’s patriarchal mindset and shows women candidates being used as a front to fulfill constitutional requirements while decision-making powers remained in the hands of men. Farzana Ali, a journalist from Peshawar, said problems with the nomination process and shortcomings in elections mechanism contribute to this problem.

Ali said the denial of women’s basic rights by family, especially brothers, opposition by relatives, continued economic dependency, and deeply rooted fear of power-sharing are among the forces keeping competent women out of policymaking at the grassroots level. Concrete examples of these phenomena persist in elections around the country, which discourages qualified candidates from running.

She said increasing women’s participation in practical politics is a great achievement in Pakistan’s history but added such victories do not mean barriers for women have been completely removed. “We should not forget that cultural taboos and patriarchy system [keep] women away from politics.”

Structural challenges

During Pakistan’s formation, influential women worked alongside men to earn the country’s sovereignty. Today, contemporary leaders like Hina Rabbani Khar, Shireen Mazari show the kind of examples women in politics can set. Still, shining examples of female leadership have not translated into greater representation in parliament. According to IPU data, a global organization of international parliaments, Pakistan ranks 112th in the world for its percentage of women in national parliaments.

Pakistan’s low percentage of women in the workforce (around 25 percent) runs counter to global trends for countries with similar income levels – a trend reflected in parliament. Barriers to entry for women running for public office don’t go away once they are elected; Women parliamentarians say they are treated differently than male colleagues within their parties and discouraged from partaking in certain activities. They speak to a political culture that puts women politicians in a separate category from men and requires them to work double-time to prove themselves.

Shahida Akhtar Ali, a Jamiat Ulema-e Islam (JUI-F) MNA, said cultural factors contribute to the distinctions political parties and the public make between male and female politicians. She said to keep women comfortable and avoid inconvenience, party leadership prefers female candidates not to get involved in public protests, adding that women from the party partake in separate protests.

Even so, she said the party’s leadership realizes the importance of women in party politics, as evidenced by her leading role in JUI-F. She added that although the party could not meet the quota for women’s representation in the previous election, they have devised a strategy to ensure fair representation in the next one.

Sannya Sabeel, a Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) leader from Manshera said when women run for elections, the most common reaction from the public is one of doubt about how a woman can “move freely in public and can lead in elections.” Women are encouraged to take part in politics but only on reserved seats, she said. Still, they face strong resistance from family, party, and society when they want to campaign.

Sabeel said it remains difficult for women to be independent in their decision-making because many still rely on family support. She said there are still many misconceptions associated with women in politics. Sabeel said if a woman parliamentarian asked for a meeting with the party leadership, for example, instead of facilitating her request, colleagues might try to hinder her. She said male colleagues have low expectations of women and think they may be requesting a meeting only to lodge complaints against colleagues.

Sabeel doesn’t think gender discrimination is involved in the allotment of tickets since parties allot tickets only after a thorough assessment of winning candidates. But she said male candidates are more likely to get tickets because they frequently attend public gatherings, which women in Pakistani society generally can’t do.

Punjab Assembly member Sumaira Gul from the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) said when she attends funerals in her constituency as a party representative, people tend to treat her like other women in the community rather than as a politician — confining her to women’s gatherings.

Since Pakistan’s social structure is patriarchal, the challenges women face in entering politics are also economic. Financial dependence is also a barrier that confines women to reserved seats, said Aliya Hamza Malik, a parliamentarian from PTI. She said financial constraints make it harder for female parliamentarians to run for general seats since campaigning for such positions requires resources. Malik said political parties can help increase women’s representation in general seats if they provide financial support to female members to run election campaigns.

Zaib Jaffar, a parliamentarian from the Pakistan Muslim League (PLM-N), said this financial problem signals the brutality of the profession in which no one wants to give up a seat once it’s won. This leads to stiff competition for seats, even within families. She said since women join the house of their husbands after marriage, some worry that if a daughter takes over a seat from her father, power will shift from one household to another.

She added that financial constraints are a major challenge since politics is a business and women mainly rely on financial support from male family members. Many families don’t dare to invest in women, which contributes to the uneven gender ratio. Without this investment, carrying out a successful political campaign is impossible for many.

Jaffar said family politics, political background, and ideology all matter in the career of female politicians. She said Pakistan’s political structure gives space to women who work hard and prove themselves, adding that the male-dominated model cannot be held fully responsible for the parliament’s uneven gender ratio. When Jaffar first contested an election in 2000, she said people in the constituency were skeptical that she would be able to compete. She argues she won the seat because of hard work.

Ali from CPDI said the existing political structure doesn’t take women members seriously. He added that women parliamentarians are placed in a separate box where they have less of a role in a party’s decision-making. As a result, gendered politics can have major structural consequences if female members are not given a say in the direction of political parties.

Women parliamentarians say male colleagues often taunt them, saying they are only in parliament because there are seats reserved for them. Due to a system of indirect elections, political parties award often allot reserved seats through nepotism and favoritism instead of qualifications.

Records reveal that female parliamentarians from many leading political parties, including the Pakistan Muslim League (PLM-N), have close familial links with the party’s leadership. This culture of nepotism isn’t reserved for women in politics, but because constraints on women are high and entry points into politics are fewer, the problem exacerbates the skewed gender ratio in parliament.

Jaffar said political background may help women establish themselves as career politicians but they still need to show strength through their work within the party and in parliament.

She argues many women in parliament don’t have family backgrounds in politics and said they become members of parliament because of their performance and capabilities. However, she recognizes harassment and intimidation as major factors discouraging women from participating in public politics.

The way forward

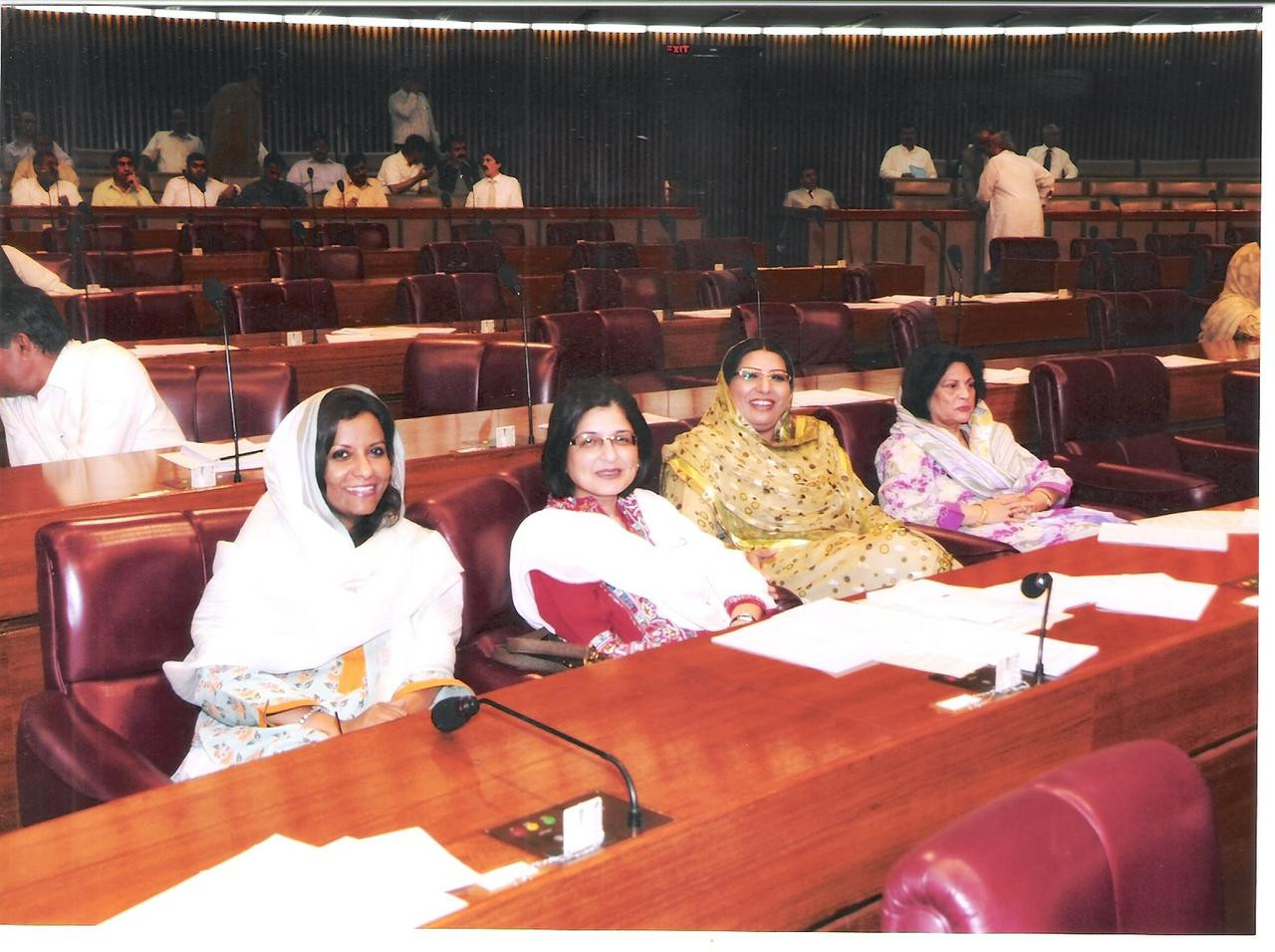

Although the numbers of women in the Parliament of Pakistan are low, their contributions are significant. According to a 2016 report by the Pakistan Institute of Legislative Development and Transparency, women are listed among the top ten best performing parliamentarians. Pakistan has also made strides towards gender equality by approving women-friendly legislation, including an anti-harassment law approved by parliament last month.

Dr. Shazia Sobia Aslam Soomro, a member of the National Assembly from the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP), said this reflects women’s active role in professional affairs. The highly competitive environment makes women more active in creating legislation, she said.

Despite low representation, Farha Naz, a freelance journalist with 35 years of experience covering politics, said female parliamentarians are generally more active in the assembly than their male colleagues. She said they frequently contributed to legislation related to gender equality, along with legislation about children and marginalized communities. Jaffar said women are generally active in the assembly, adding that male members are often found sitting in the gallery while the women are in the Session. “It is not self-praise, but a fact,” she said.

Jaffar added that there should be a greater understanding among male politicians of equality for politicians from both genders under law. Jaffar said Pakistani society sees women as delicate, sensitive, and suitable to domestic affairs. She said the same perception is found among male colleagues. “It’s society’s dilemma,” she said.

Pakistani society is tough on women – public reactions to events involving women oscillate between blame and victimization. Jaffar contends this victimization puts women in a separate category than men, creating a gendered explanation for every problem or emergency situation, which is ultimately harmful for women’s role in society. She believes the only people who will be able to change the system are women by helping and supporting each other instead of blaming men.

Dr. Soomro said success for women also depends on political parties trusting women’s capabilities, acknowledging their performance, and supporting them in public politics. She said the traditional view that women are destined for domestic affairs and religious interpretations that keep women out of the public eye dually limit active participation among women in politics. She said until Pakistani society changes its perception about the role of women, participation in politics will remain low.

There are women parliamentarians in the assemblies on reserved seats who could contest elections on general seats to establish grounds for women to participate in practical politics, Ali from CPDI said. For this to happen, political parties would need to throw support behind female candidates at the same level as they do male party members.

Gul said all political parties should ensure a direct method of election to avoid allotting tickets to women candidates who are running directly against their male colleagues to increase the chances of women winning general seats.

Women parliamentarians belonging to different political parties agree that increasing women’s representation in parliament is important. Many argue for an increase in the quota of tickets political parties allot for women in general seats from 5 percent to 25 percent; Dr. Soomro from PPP said during electoral reforms, women parliamentarians demanded an increase in the reserved seats to bring it up to 25 percent but the recommendation was rejected by ‘the incumbent government’.

Still, some women are happy with winning parliamentary seats through the current quotas. Malik from PTI said she would prefer to be on a reserved seat in the future because she can’t afford to fund a campaign, adding that if her party supported her financially she would run for a general seat.

Dr. Soomro said women can run more successful political campaigns than men because they have direct access to houses and aren’t constrained to public meetings, and other societal factors. “What women parliamentarians can do, men cannot.”