By Steve H. Hanke

Published in nationalreview.com on April 08, 2022

Last weekend, Pakistan’s Prime Minister Imran Khan attempted to side-step a much-anticipated vote of no confidence by pointing fingers at unnamed foreign regime-change agitators and advising President Alvi to dissolve Pakistan’s Parliament. But yesterday, Pakistan’s supreme court overruled the dissolution of Parliament and set Khan’s vote of no confidence for Saturday morning. Just what provided the opening for Pakistan’s political turmoil? The economy — namely, the recent surge in inflation.

To get a handle on how the economy works and where it’s going, one needs a model of national-income determination. For me, a monetary approach to national-income determination is what counts. Indeed, in a fundamental sense, it’s a theory of everything. The close relationship between the growth rate of the money supply and nominal GDP is unambiguous and overwhelming.

So, what is Pakistan’s current monetary temperature? Let’s first determine the “golden growth” rate for the money supply for the period 2010–2019 — in other words, the trend rate of broad money growth that would allow the State Bank of Pakistan to hit its inflation target. Let’s then compare the actual growth rate of Pakistan’s money supply with the golden-growth rate. To calculate the golden-growth rate, I use the quantity theory of money (QTM). The QTM states that MV = Py, where “M” is the money supply, “V” is the velocity of money, “P” is the price level, and “y” is real GDP.

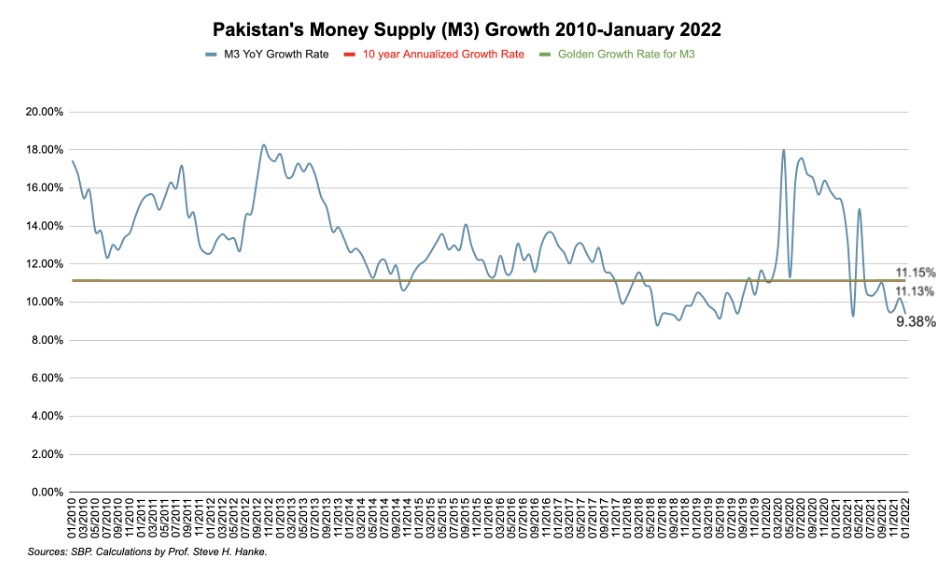

According to my calculations, Pakistan’s average annual percentage real-GDP growth from 2010–2019 was 3.9 percent, average annual growth in total money supply (M3) was 11.1 percent, and average annual change in the velocity of money was 0.3 percent. Using these values and the State Bank of Pakistan’s average inflation target of 7.6 percent, I calculated Pakistan’s golden-growth rate for broad money (M3) to be 11.2 percent.

How did I get there? I rearranged the QTM identity and solved for “M.” The golden-growth rate is the inflation target plus average real-GDP growth minus the average percentage change in velocity. Pakistan’s golden-growth rate, then, is: 7.6 percent + 3.9 percent – 0.3 percent = 11.2 percent.

So, for 2010–2019, the average growth rate of the money supply (M3), which was 11.1 percent, essentially matched the golden-growth rate of 11.2 percent. This resulted in an average realized inflation rate of 7.8 percent per year for that period, which came very close to meeting Pakistan’s inflation target of 7.6 percent per year — overall, a pretty good performance.

Note, however, that since the Covid‐19 pandemic began in March 2020, the growth rate in M3 began to skyrocket, thanks to a dramatic surge in credit to the public sector. Monetary growth peaked at 18 percent per year in April 2020, and at the end of 2020, M3 was still growing at 15.9 percent per year. That rate exceeds the golden-growth rate of 11.2 percent per year by a significant margin. As a result, inflation is officially reported to be soaring at 12.2 percent per year. In fact, according to my measure, which is based on purchasing-power parity and high-frequency data, Pakistan’s actual realized inflation rate is more than double the official rate: a whopping 30 percent per year.

There’s one more important item worth stressing. Currently, M3 is growing at 9.4 percent per year, under the golden-growth rate of 11.2 percent per year. Why, then, is there inflation? The answer lies in the time lags between changes in the rate of growth in the money supply and inflation. As a general rule, these long and variable lags are anywhere from twelve to 24 months. Since M3 began growing egregiously about 24 months ago, it’s no surprise that Pakistan is in the grips of inflation today. This, of course, is creating a big problem for Prime Minister Khan.

Is Khan to blame for Pakistan’s inflation woes? If not, he certainly is the fall-guy. Khan is paying the price for the State Bank of Pakistan’s actions dating back to March 2020. Like many central banks that followed in the Federal Reserve’s footsteps, the State Bank of Pakistan had a knee-jerk, panicked reaction, and slammed the monetary gas pedal to the floor as soon as Covid reared its ugly head. Two years later, Khan is suffering from the political fallout of that decision. It isn’t the first time a central bank has done in a prime minister, and it won’t be the last.