Matiullah Khan was a construction worker from Mianwali who was hired by a Dubai-based company in 2015 on a three-year visa. Like millions of others, he went there to increase his daily wages, to set aside some savings, and to remit money back home so that his family had food in their mouths and shelter over their heads.

Once his visa expired and his employers did not renew it, Matiaullah was unwilling to go back home. He hoped some other employer would pick him up. Instead it was the shurtas [Emirati policemen] who did. He subsequently spent two years in a crowded prison, along with several other Pakistanis who ended up sharing the same fate.

As the pandemic raged during the summer of 2020, the rate of the Covid-19 spread in prisons triggered a repatriation of 1,200 inmates from the UAE back to Pakistan, along with 75,000 other workers who were returning after losing their jobs in the economic crunch. Matiullah was one of those repatriated.

Even now, despite a global disease and financial spirals, Saudi Arabia hosts around 2.6 million Pakistani citizens and the UAE 1.2 million. Qatar, Oman, Kuwait and Bahrain make up another 0.6 million. There are over four million Pakistani expatriates in Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries.

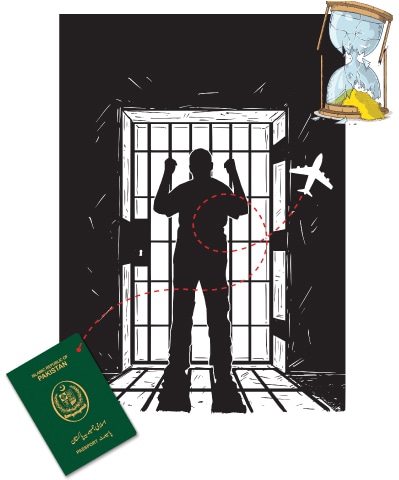

Not all of them are working class migrants, but a report by the Bureau of Emigration & Overseas Employment (BEOE) says it has registered more than 11 million Pakistanis under ‘labour force’ heads to different parts of the world from 1971 to 2020. Gulf countries such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE were their biggest destinations, soaking up about 96 percent of this registered migrant labour. There are many who travelled unregistered too. All with the same ambitions as Matiullah.

According to the Ministry of Overseas Pakistanis and Human Resource Development (MOPHRD), 52 percent of these migrants originated from Punjab, 26 percent from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and 9.5 percent from Sindh. A mixture of unskilled and semi-skilled workers, they apply for low-income jobs such as welders, masons, carpenters, plumbers, labourers or farmers, jobs that local, financially better off Arabs don’t want to do.

Hence the insatiable demand for migrant labour — and with more population than employment opportunities, it’s a demand that South Asian nations such as Pakistan are happy to meet. Remittances contributed roughly seven percent of our GDP from 2013 to 2019, a number that has soared towards a 10 percent average in the last two years. Globally, we are the fifth highest recipients of remitted money.

A record high of remittances was hit in 2020-21 of 29.4 billion dollars, compared to 18 billion five years ago. This is something Prime Minister Imran Khan has praised again and again, saluting these efforts from a distance with much pride and gusto, but without perhaps recognising the burdens borne to remit that money back. The current regime calls expatriate workers Pakistan’s best export. But exported under what choice and circumstances? Not everyone leaves their homes and homelands with a light heart, and how much personal agency do they retain wherever they end up? What kind of living conditions do they have to accept to be saluted thus?

Workers remit billions in dollars — those from Saudi send over 7.5 billion dollars annually, according to the State Bank of Pakistan — but at the risk of life and limb; they are often considered the lesser humans in the GCC countries, the lesser Muslims despite sharing the same faith.

Drug trafficking, theft and violation of immigration laws make up the large majority of these crimes. The vast majority of overseas Pakistanis in GCC prisons are arrested over possession of drugs, around 4,000 in total. Illegal emigration and expired visas wrack up another 1,500 arrests. Fraud and petty crimes round up the last 2,000 arrests.

Local courts attend to the cases without any intervention from the Pakistani state machinery, the consulates, the embassies; the workers count their days in jail while we only count their remittances. There are rarely any Prisoner Transfer Agreements, only circumstantial deportations and repatriations at the whims of host countries.

The accused lack access to legal assistance and spend months in prison without formal charges or trials. They’re given ineffective or misleading translation services that pressure them into confessions in a language they don’t understand, in a justice system that is alien to them.

Imagine hundreds of people lined up on death row, sleeping inches away from each other on the floor, deprived of food and water for long durations, man upon man in every corner. Imagine seeping sewage and a cesspit of clogged toilets they dread to use. If the unwashed cages aren’t dehumanising enough, imagine getting routinely beaten or shocked with electrical devices by the guards during needless interrogations, for confessions the system is rigged to collect anyway. This is the ordeal those in jails have to go through, as recollected by multiple prisoners during interviews after their release.

All this for having produced heroin packets from various bodily orifices without anyone asking how they got there. Imagine never getting to explain your side of the story because your side of the story is in another language, from another part of the continent. Here, you’re just a drug mule ready for sentencing.

Her elder son, Mehboob Alam, was a bit sceptical about this request. He opened the tiffin box to confirm that there was indeed just halwa on the top. But after Jameela Bibi’s flight reached its destined time in Jeddah, her family lost all contact with her for a month. She finally called from a borrowed phone over 30 days later.

She said she was in a Saudi prison, that she’d been sentenced by a court, that she was made to accept a confession. Then she confirmed her son’s worst fears, that just under the halwa, airport security found three packets of heroin as the tiffin box ran through their scanners.

When Mehboob found this out, he went in search of the woman who had handed his mother that fateful box. He discovered that the woman had her own son caught with heroin at Sialkot airport at the time. Mehboob and his brother lodged complaints against her and the FIA locked the mother and son up, but they were both later released, he found out, without any formal charges pressed. “They are a mafia, they have contacts higher up, there’s nothing we can do to them,” Mehboob says. “We have to live in the same village so we took a step back and decided to wait it out.”

The wait was an eternity. His mother’s initial 15-year sentence was lenient, because she was an old woman on her own, because she was there for an Umrah, because she looked baffled as to what it is they’d found in that steel container other than a popular confectionery. The sentence was later commuted down to five years, which was reduced further by six months. Jameela Bibi is awaiting deportation documents these days. In Saudi Arabia, the legal system works at the judges’ discretion. There’s a scarcity of coded legislation and unified rulings over the same crimes, or what sentences they necessitate.

During a visit to Pakistan by Prince Muhammad bin Salman in 2019, it was announced that 2,107 Pakistani prisoners would be released from Saudi jails. Only 579 had been released six months later | AFP

A joint JPP and Human Rights Watch (HRW) report from 2018 suggests that the Saudi legal system is an interpretational assortment of Islamic law, some formal, some informal. In the absence of a written penal code, the adjudicators are judge, jury and executioner; making charges and sentences up as they go along, not beholden to judgments from the past, not beholden to criticism from the present or future.

There is no mandatory death penalty for drug smuggling, the sentence is completely up to the judge’s discretion, and often the judge’s mood. You can get five years or you can get a swift beheading. You can get 25 years or 15. Sometimes the death penalty becomes a 15-year sentence by virtue of leniency, sometimes a 15-year sentence becomes a death penalty by virtue of cruelty.

The prisoners don’t even know how their guilt will be established under the Sharia Law. It could require witnesses or a written confession or trial by character or trial by implication; it could have requirements Pakistani citizens have never heard of.

Jameela Bibi’s case is not unique. The same thing happened around the same year to one Zohra Bibi, living in a low-income area of Johar Town Lahore. She’d made a new friend in the neighbourhood who offered her an Umrah package with all the passports and documentation prearranged.

Her younger son, a tailor whom she helped with his work, was asked to accompany her to the Islamabad airport to see her off, which they found strange, because they could have taken a flight from Lahore. They found it even stranger when the mother was taken to Multan and told the flight to Jeddah was from there, and the younger son was asked to stay in a rundown motel in Islamabad.

Muhammad Naveed, the elder son, recounts all of this to me in amazement. A painter, a seasonal labourer and a father of four, he was out of town when these life-altering decisions were taken.

Two days later, Naveed returned to a house without a brother and a mother. And a few days later, he got a call from an unknown number, it was his mother on the other line, crying, saying it was a fraud, that they caught her at Jeddah airport with drugs in her purse.

The visa agents had forced the drugs in there, on the threat of shooting her younger son who was still in Islamabad with the other subagents, if she refused. She didn’t. She couldn’t. She boarded that flight knowing that she was headed for drug trafficking and not spiritual affirmation.

The judge was very lenient in her case and gave her a five-year sentence and eventually a rehmat that set her free. She’s been awaiting deportation for the last eight months.

There are just two things Naveed can’t understand or forget. “How can our scanners catch people bringing contraband in tyres and mattresses but can’t catch purses and phones full of heroin going out?” he asks. “The authorities must be complicit,” he says.

The second thing he can’t forget is that when his younger brother expressed concerns on that carousel between Lahore, Islamabad and Multan, the immigration sub-agents reply was, “have no fears, I assure you she will be treated like I treat my own mother.” Two days later, she was in jail with drugs. It shook Naveed to the core, for someone to say something so sacred and then act so profane.

They get lengthy and informal detentions without any clarity in charges or a fair trial. Left in a haze of confusion, they eventually sign on to arbitrary, predetermined prison sentences they do not understand, with no options but to hope for a miracle someday.

A man sentenced to five years in Saudi Arabia for having his work visa not renewed within the time limit, refused to sign the mandatory confession letter as it was his Kafeel, his sponsor, who delayed the process because of a dispute between them. Two hearings later, the judge still had one thing to say: sign the confession letter. He eventually gave in after his fourth hearing because he had already served six months. The only thing he was achieving was adding more trials to his tribulations.

Arab court officials pressure defendants into stamping papers with their fingerprints and consider that an acceptance of charges and judgments, without letting them understand what those are. Arabic is slightly comprehensible to Pakistanis because of the script but is still a distant language. One formerly incarcerated man told the JPP that he accepted a conviction on charges of alcohol consumption after the judge told him that his sentence would be ten days in prison and 80 lashes. He considered that acceptable punishment in the grand scheme of things. He was later shocked to discover, to his great regret, that signing off on the sentence also meant his deportation with immediate effect.

On August 3, 2021, another 28 prisoners were deported back to Lahore from Saudi Arabia, the last reported instance of this slowly unfolding saga.

In television interviews, one of the returnees, a man named Munawar Khan from Kurram Agency, explained that he went to Saudi Arabia five years ago as a construction worker. A friend of his told him to take an iPhone for someone as a gift. The Saudis scanned the phone and found heroin inside. His initial sentence was death by decapitation, under the qisaas law, which was then commuted down to 15 years, until the diplomatic intervention set him free this year.

He used to cry on the phone with his wife, on the phone with his son, on the phone with his brother. “I feel like I’m living a second life, it felt like my first one ended there, ended with the qisaas sentence.”

All the prisoners deported in August were from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. In media interviews some of them have said they left Pakistan as a result of the internal displacement that took place during the drawn out ‘War on Terror’ and military operations. Some eventually ended up in Saudi jails for fraud, trying to make money when Covid-19 first hit and their legal jobs weren’t operational or paying. Some were in for an expired resident permit, an Iqama, the renewal of which is the responsibility of one’s Kafeel.

Some still haven’t gotten the chance to avail that open pardon.

Prisoners returning from Saudi Arabia in July this year celebrate after landing in Pakistan | APP

Since ratifying the Vienna Convention in 1988, Saudi Arabia has an obligation to inform Pakistani consular officials or the embassy when they arrest any of its citizens. They don’t. Saudi Arabia is also one of the few countries left in the world that imposes corporal punishment such as public flogging.

Most Pakistani migrants are held in detention for longer than the six-month period permitted without producing them before a court of law. They get no mandatory phone calls; they need to borrow stolen phones in prison to inform their families. Saudi Arabia finally approved public defender services in 2010 but migrant labourers are rarely provided one, and they cannot afford private lawyers.

One judicial sentence I read about in the JPP report was of a 15-year jail term with a 50,000 riyal fine and 1,500 lashes. That is triple punishment for one crime — the crime of being an impoverished migrant.

One man served a 10-month sentence for transporting drugs in his taxi. The taxi was his, the luggage and the drugs in them weren’t. He represented himself in court and got off lucky; on a bad day it could have been 10 years. On the worst days it could have been death.

“In contravention of international human rights standards, which does not allow for capital punishment for nonviolent drug crimes, since the beginning of 2014, Saudi authorities have executed 163 individuals, including 61 Pakistanis,” says the JPP and HRW report.

There’s a term in Urdu, khud-kafeel. It means self-reliant. Borrowed from Arabic, the word kafeel, without the preceding khud, takes on a more sinister explication. A Kafeel is someone you’re dependent on. In Gulf countries, a Kafeel is someone responsible for bringing you inside their borders, the one who gets your work visa and renews it, the one who decides what occupation you can do, where you can live, where you can travel, when you can leave the country, and when you can abandon or change your employment.

It’s a sanitised form of serfdom, modern day slavery, where the chains are invisible but just as burdensome. Even the Qataris who claim to have abandoned Kafalat still use a system eerily similar to it, still with a sponsorship visa and everything that entails. Kafalat has no basis in Islamic law but is ubiquitous in GCC countries.

If your Kafeel forgets to renew your visa, the criminal fine is placed upon you, the labourer, not the state national who is irreproachable. If you make a mistake or if you upset your Kafeel, he can have you deported. If your Kafeel turns abusive, you can’t go to the police, because who will listen to a slave? Saudi Arabia has promised to abolish the Kafala system and give workers the freedom to change employers and the right to exit the country without their employer’s permission. But as of 2021, it remains a promise still in the process of being implemented.

Migrants to Gulf countries are still stuck with Kafeels who do not care about the well-being of the people they sponsor. There are myriad stories from workers in the Middle East. Stories about forced labour or financial extortion for visa renewals and exit permits.

Stories about 20 people sleeping in a room the size that’s meant to hold six. Stories about being unable to breathe from the heat and the claustrophobia, then waking up to go do manual labour under the scorching desert sun, while always watching over your shoulder for a shurta or an immigration agent or the company that’s sponsored your existence in a concrete oasis. Stories about looking in your pockets to make sure you have a legally recognised Iqama, the residence permit a Kafeel gets you.

As the JPP report says, “In 2017, only 2-3 percent of workers going abroad for employment used the Overseas Employment Corporation.”

So how is most of the labour force making its way to the Gulf states? Through intermediaries, through subagents, through networks of friends and relatives who are already in the host countries, or through returned migrants.

Many floundering in Gulf prisons have been caught using ‘Azad Visas’, which can be bought and sold in an unregulated “migration market”. Individual visas not filtered through company contracts are granted by the governments of the GCC countries to Kafeels for the hiring of domestic workers and household staff. Turn that individual visa over to a black market and it becomes a direct entry into the nation, with no obligatory vocation.

‘Azad Visas’ are sold to those wishing to come to the Gulf and try multiple things, run their own businesses, find several streams of revenue, hence make more money — free of oversight, Foreign Service Agreements and employment contracts. It goes without saying that ‘Azad Visas’ are illegal everywhere in the Gulf.

The JPP report goes on to say that “OEPs are required by law to advertise positions in newspapers. But instead they make announcements in mosques or delegate recruitment to subagents or put notices on walls, because the organisation simply doesn’t have the capacity to go over Pakistan’s rural immigration market.”

These recruitments are illegal too.

The Emigration Ordinance 1979 sought to remedy this with mandatory briefings for outgoing migrants, to protect them from illegal and fraudulent recruitment practices. A survey conducted in 2007 by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) discovered that only 10 percent of their respondents attended these briefings.

Despite First Information Reports filed by families of victims against fraudulent immigration agents, none of the OEPs or their subagents have ever been charged. Only in one of the cases documented in the JPP report was an OEP arrested in Khushab, only to be set free 12 days later. Even when the Federal Intelligence Agency (FIA) catches a fraudulent subagent, there are no witnesses ready to come forth, because they and their families feel like they might need the services of this subagent again someday.

The lack of coordination between the FIA, the police and other state agencies, including the BEOE, puts the lives of Pakistani migrant workers in danger.

Hashish, cocaine and MDMA can get to Dubai through multiple sources, but heroin is supplied exclusively from Afghanistan’s poppy plantations, often through Pakistan and on to the Gulf countries.

The Dubai police said these Pakistani nationals were making people smuggle drugs inside their bodies despite the fatal risk of the capsules exploding inside. Yet it’s been 9 years since then, and the heroin trafficking and Gulf imprisonment goes on unabated.

State level organisations are so unresponsive that there’s a Welfare Committee of Pakistani Associations in Dubai that visits jails and offers legal counsel, because our official consulates don’t. They’ve even managed to get prisoners free who were in there over bad cheques or outstanding payments. Exasperated committee workers are doing what our diplomatic state machinery should be doing in the first place. Not leaving behind citizens unheard, unnamed, uncared for.

One Zaiba Bibi from Larkana, whose husband has been in prison in Dubai for 11 years over murder charges, just wants to know why it took so long for her to find all this out. He went as a labourer for a construction company and then like everyone else in this story, simply disappeared.

Zaiba Bibi wouldn’t find out for five months that his phone had stopped ringing because a murder trial was going on. She didn’t know when the charges were announced. And when the sentence of 25 years came out, the consulate made no effort to inform her. Zaiba Bibi had to scrounge around for scraps of information, having no contacts in Dubai of her own, from other returning migrants from there to Larkana.

She didn’t know if her husband was given a lawyer or not. She didn’t know what the exact incident was. She didn’t know if he was going to be deported and sent to jail here or kept there. She didn’t know when she could talk to him again, when she could tell him that he has a son in 11th grade and that she’s been fending for herself for over a decade. Because what was once her husband is now just a ghost in a distant land.

Sadly, hers is far from the only ghost story from Arab lands.